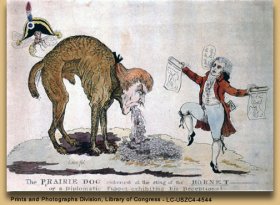

By James Akin (1773-1846).

Hand-tinted engraving on pale blue-grey laid paper.

Original size, 28.5 x 40.6 cm (11.22 x 15.98 in.)

Thomas Jefferson is satirized as an emaciated dog with his obviously docked tail ending in a few scraggly hairs, and a prominent organ between his extremely long hind legs—a lewd reminder of Jefferson's scandalous liaisons with his mulatto concubine, Sally Hemings. Goaded by a stinging bee (the official symbol of Napoleon's Second Empire) sporting a Napoleanic cocked hat, "dog" Jefferson vomits "Two Millions" of dollars on the prairie. Facing him, James Monroe holds a map of "West Florida" in his proper right hand and a map of "East Florida" in his left. From his left pocket protrudes a list of instructions from Talleyrand. The dialog balloon at his lips reads "A gull [deception] for the people."

The background of Akin's cartoon was this: Jefferson had assumed that the Louisiana Purchase included West Florida. When he discovered that it did not, he immediately (in 1804) sought to carry out a secret plan with Congress—with encouragement and support from France—to buy it from Spain for $2, 000, 000. His scheme failed, but the issue was eventually resolved by John Quincy Adams, Secretary of State under President James Monroe, in the Adams-On"s Treaty of 1819.

For many years it has been thought that this very famous cartoon was published in the Newburyport, Massachusetts, Herald sometime in 1804.However, the species that was sometimes called "prairie dog" (which in 1815 naturalist George Ord (1781-1866) was to officially name Arctomys ludoviciana ["bear-mouse of Louisiana"]) was entirely unknown to easterners until Meriwether Lewis sent a caged live specimen to President Jefferson from Fort Mandan on the same day the expedition resumed its journey up the Missouri.

That was on April 7, 1805. Forty-three days later the expedition's barge, on which the "barking squirrel" began its long journey, reached St. Louis. It was sent on down the Mississippi by barge to New Orleans, carried by sea to Baltimore and then by land to the capitol, arriving—alive!—in Washington on August 12. Jefferson was at Monticello, but his maitre d'hotel, Etienne Lemaire, placed "the kind of squirrel . . . in the room where Monsieur receives his callers." The first word of the new species to leak out of the personal correspondence pipeline was in a letter that Clark wrote to William Henry Harrison, and dispatched on the barge headed for St. Louis. The letter was published in the Baltimore Telegraph and Daily Advertiser on July 25. Clark informed the governor that in what he had so far seen of Louisiana, there was "a great variety of wild animals . . such as . . . the ground prairie dog." On October 6 Jefferson, who had returned to Washington, wrote to Charles Willson Peale that Captain Daniel Cormack, of the U.S. Marines, was soon to carry the "burrowing squirrel . . . a species of Marmotte" to Philadelphia for display in Peale's Museum. On October 22 Peale informed Jefferson that the "living Marmotte . . . a handsome little Animal" was thriving. Jefferson returned to Washington in late September, and on October 9 informed Charles Willson Peale that a U.S. Marine, Captain Daniel Cormack, would be carrying the "Marmotte" to Philadelphia for display in Peale's Museum.

Harry Croswell, the fiercely anti-Jeffersonian editor of an Albany newspaper, either personally got a peek at the animal in Jefferson's reception room—doubtful, considering the distance he would have had to travel—or received a written description of it from an anonymous conspirator. In any case, he seized the opportunity to impugn Lewis's qualifications as a naturalist in a short paragraph on "Louisiana Curiosities, " dated September 17. Writing over one of his several pseudonyms, "Alex. D. Adv., " he insisted that Lewis wasn't smart enough to see that his so-called prairie dog was only an eastern fox squirrel that had "lost part of the hair from its tail on the journey." Of course, nobody was around yet to counter the canard, but all this is enough to strongly suggest that Akin could not have conceived his satirical cartoon until sometime after he read Croswell's shaggy-dog story, and after there was a readership that could understand his own punch line. Sometime after September 17, 1805.

Akin declared his authorship of the cartoon in the Newburyport Herald of November 14, 1806, but did not specify the date on which it was published. James C. Kelly and B. S. Lovell, "Thomas Jefferson: His Friends and Foes, " The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 101, no. 1 (January 1993), 150.

Harrison was the governor of Indiana Territory; his office was in Kaskaskia, in the Illinois country.

Jackson, Letters, 1:267.

"Louisiana Curiosities, " Balance and Columbian Repository, vol. 4, no. 38 (September 17, 1805), 304. American Periodicals Series Online. Maureen O'Brien Quimby, "The Political Art of James Akin, " Winterthur Portfolio, vol. 7 (1972), 67-68. Lewis was well aware that the tail of an eastern fox squirrel (Sciurus niger) is typically half as long as its body, which qualifies it as a bona fide Sciurus—shade-tail. Furthermore, Croswell failed to get the word that Lewis's new species of squirrel was a burrower; the fox squirrel is a tree-dweller.