Pretrial risk assessments are beginning to catch on among California law enforcement agencies. As reported in last week's feature story, "Barred From Freedom, " Santa Clara, Sonoma, Yolo, Marin, Napa, and Santa Cruz counties have each implemented some form.

Pretrial risk assessments are beginning to catch on among California law enforcement agencies. As reported in last week's feature story, "Barred From Freedom, " Santa Clara, Sonoma, Yolo, Marin, Napa, and Santa Cruz counties have each implemented some form.

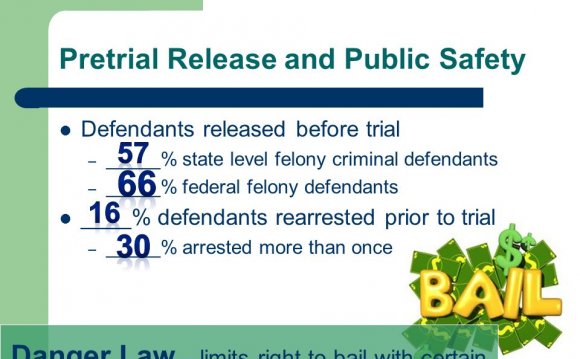

The basic idea of pretrial risk assessment is to use evidence-based methods to quantitatively predict how likely a defendant is to skip a court date or endanger the public. Instead of the inmates freedom depending on whether he has enough money to pay bail, his freedom hinges on various risk factors, such as employment history, community ties, residence stability, and more. Low risk inmates can be released on their own recognizance (OR), and moderate risk ones can receive probation-style supervised release, like electronic monitoring.

But while pretrial risk assessments are growing popular now, the concept has been around for at least 50 years.

In 1961, a retired businessman and chemical engineer named Louis Schweitzer, New York City Mayor Robert Wagoner, and a journalist named Herbert Sturz established the Manhattan Bail Project, which sought to increase the rate of releases on own recognizance. Sturz came up with the idea, Schweitzer funded it, and Wagoner helped it get political backing.

The endeavor came amid America's first serious bail-reform movement. For three-plus decades academics had been publishing studies asserting that pretrial freedom was primarily based on a person's wealth. Advocates and officials, like Schweitzer and Wagoner, eventually jumped on board.

The project, the debut initiative for the Vera Institute of Justice, was pitched as a one-year study of the bail system, an experiment in public policy. It established a point system - which considered factors like a defendant's previous convictions, community ties, and employment history - in an effort to quantitatively measure a defendant's flight risk, and determine whether or not to recommend OR to the judge.

Court transcripts from the project's first year show how the recommendations worked. On March 30, 1962, for example, a man named Manuel Ortiz, facing grand larceny charges, stood before a judge at an arraignment hearing:

Court-appointed defense attorney Austin Canade: Kindly request parole, your honor.Judge Manuel Gomez: Go into it.

Canade: The following has been verified by the Vera Foundation. Residence, Mr. Ortiz has been living at the above address for the past five years, 75 LaSalle Street, New York, with his mother who is present in Court. He's been living in New York for his entire life. He is helping to support his mother by contributing $35 a week. Employment, Mr. Ortiz has been working the last five months at A. Bearing Manufacturing Company ... [transcript ink is faded for several words]... and for prior reasons, request that defendant be paroled. I don't know what his record it, if he has any.

Judge: He has no previous. Has he been cooperative, Officer?

Bridge Officer Gennaro Lupi: Yes.

Judge: Any objection to parole?

Assistant District Attorney Norman Ostrow: No objection.

Judge: Defendant is paroled. You are advised to show up here April 3rd. Failure to do so besides this charge, you will face an additional charge on parole jumping.

A study of the project's first three years showed that judges followed the recommendation 59 percent of the time - a control group not assessed by the project had an OR rate of 16 percent. Only 1.6 percent of those granted OR through the project failed to appear in court. The results suggested that "people with strong ties to the community could be safely released from custody without bail merely on their promise to return to court, " Jerome E. McElroy explains in Introduction to the Manhattan Bail Project. A national push for bail reform soon followed.

By 1965, more than 50 jurisdictions had installed similar systems, and U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy was fresh off holding his first National Conference on Bail and Criminal Justice. A year later, Congress passed the Bail Reform Act of 1966, which declared that defendants in non-capital crimes had a right to be released on OR, and that pretrial incarceration would be a last resort, used after a judge deemed all other alternatives insufficient.

But the movement would meet a backlash. As the feature explained:

Rising crime rates through the 1970s and '80s, however, shifted this paradigm, as law enforcement officials argued that judges must also consider the potential danger a defendant poses to society. States, including California, amended their laws so that public safety would also be a primary factor in pretrial decisions. Congress followed suit with the Bail Reform Act of 1984, rolling back previous reforms.Like slim-fit suits and skinny ties, though, the policy has cycled back back into fashion.

Follow @sfweekly