When in 1873 Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner entitled their co-authored novel The Gilded Age, they gave the late nineteenth century its popular name. The term reflected the combination of outward wealth and dazzle with inner corruption and poverty. Given the period’s absence of powerful and charismatic presidents, its lack of a dominant central event, and its sometimes tawdry history, historians have often defined the period by negatives. They stress greed, scandals, and corruption of the Gilded Age.

When in 1873 Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner entitled their co-authored novel The Gilded Age, they gave the late nineteenth century its popular name. The term reflected the combination of outward wealth and dazzle with inner corruption and poverty. Given the period’s absence of powerful and charismatic presidents, its lack of a dominant central event, and its sometimes tawdry history, historians have often defined the period by negatives. They stress greed, scandals, and corruption of the Gilded Age.

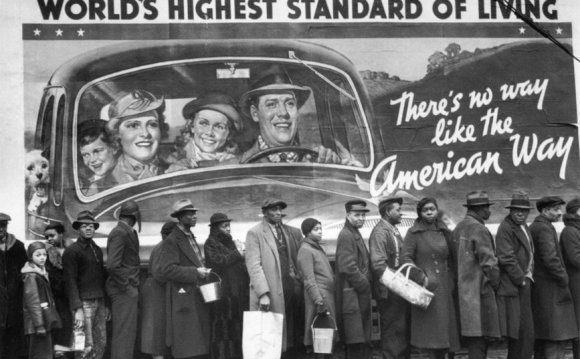

Twain and Warner were not wrong about the era’s corruption, but the years between 1877 and 1900 were also some of the most momentous and dynamic in American history. They set in motion developments that would shape the country for generations—the reunification of the South and North, the integration of four million newly freed African Americans, westward expansion, immigration, industrialization, urbanization. It was also a period of reform, in which many Americans sought to regulate corporations and shape the changes taking place all around them.

The End of Reconstruction

Reforms in the South seemed unlikely in 1877 when Congress resolved the previous autumn’s disputed presidential election between Democrat Samuel Tilden and Republican Rutherford B. Hayes on the backs of the nation’s freed blacks. A compromise gave Hayes the presidency in return for the end of Reconstruction and the removal of federal military support for the remaining biracial Republican governments that had emerged in the former Confederacy. With that agreement, Congress abandoned one of the greatest reforms in American history: the attempt to incorporate ex-slaves into the republic with all the rights and privileges of citizens.

The United States thus accepted a developing system of repression and segregation in the South that would take the name Jim Crow and persist for nearly a century. The freed people in the South found their choices largely confined to sharecropping and low-paying wage labor, especially as domestic servants. Although attempts at interracial politics would prove briefly successful in Virginia and North Carolina, African American efforts to preserve the citizenship and rights promised to black men in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution failed.

The West

Congress continued to pursue a version of reform in the West, however, as part of a Greater Reconstruction. The federal government sought to integrate the West into the country as a social and economic replica of the North. Land redistribution on a massive scale formed the centerpiece of reform. Through such measures as the Homestead and Railroad Acts of 1862, the government redistributed the vast majority of communal lands possessed by American Indian tribes to railroad corporations and white farmers.

To redistribute that land, the government had to subdue American Indians, and the winter of 1877 saw the culmination of the wars that had been raging on the Great Plains and elsewhere in the West since the end of the Civil War. Following the American defeat at the Battle of the Little Bighorn the previous fall, American soldiers drove the Lakota civil and spiritual leader Sitting Bull and his followers into Canada. They forced the war leader Crazy Horse to surrender and later killed him while he was held prisoner. Sitting Bull would eventually return to the United States, but he died in 1890 at the hands of the Indian police during the Wounded Knee crisis.

The defeat of the Lakotas and the utterly unnecessary Nez Perce War of 1877 ended the long era of Indian wars. There would be other small-scale conflicts in the West such as the Bannock War (1878) and the subjugation of the Apaches, which culminated with the surrender of Geronimo in 1886, but these were largely police actions. The slaughter of Lakota Ghost Dancers at Wounded Knee in 1890 did bring a major mobilization of American troops, but it was a kind of coda to the American conquest since the federal government had already effectively extended its power from the Atlantic to the Pacific.

The treaty system had officially ended in 1871, but Americans continued to negotiate agreements with the Indians. The goal of these agreements, and American land policy in general, was to create millions of new farms and ranches across the West. Not satisfied with already ceded lands, reformers—the so-called “Friends of the Indians” whose champion in Congress was Senator Henry Dawes—sought to divide reservations into individual farms for Indians and then open up most or all of the remaining land to whites. The Dawes Act of 1887 became their major tool, but the work of the Dawes Commission in 1893 extended allotment to the Creeks, Cherokees, Seminoles, Chickasaws, and Choctaws in Indian Territory, which became the core of the state of Oklahoma. Land allotment joined with the establishment of Indian schools and the suppression of native religions in a sweeping attempt to individualize Indians and integrate them one by one into American society. The policy would fail miserably. Indian population declined precipitously; the tribes lost much of their remaining land, and Indians became the poorest group in American society.

Immigration

Between 1877 and 1900 immigrants prompted much more concern among native-born white Americans than did either black people or Indian peoples. During these years there was a net immigration of approximately 7, 348, 000 people into the United States. During roughly the same period, the population of the country increased by about 27 million people, from about 49 million in 1880 to 76 million in 1900. Before 1880 the immigrants came largely from Western Europe and China. Taking the period between 1860 and 1900 as a whole, Germans comprised 28 percent of American immigrants; the British comprised 18 percent, the Irish 15 percent, and Scandinavians 11 percent. Together they made up 72 percent of the total immigration. At the end of the century, the so-called “New Immigration” signaled the rise of southern and eastern Europe as the source of most immigrants to America. The influx worried many native-born Americans who still thought of the United States as a white Protestant republic. Many of the new immigrants did not, in the racial classifications of the day, count as white. As the century wore on, they were increasingly Catholic and Jewish.

Immigrants entered every section of the country in large numbers except for the South. They settled in northeastern and midwestern cities and on western and midwestern farms. The Pacific and mountain West contained the highest percentage of immigrants of any region in 1880 and 1890.

RELATED VIDEO