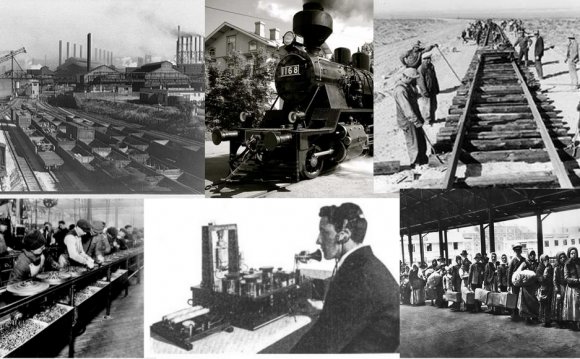

Three closely related factors—industrialism, nationalism, and imperialism—soon combined to reinforce American enthusiasm for technology as a key element of national policy. By the end of the nineteenth century, the first industrial revolution (begun in England and concerned with adding steam power to manufacturing) yielded to a larger, globally oriented second industrial revolution, linked to broader systems of technological production and to imperialistic practice. In contrast to the first industrial revolution, which was regional and primarily affected manufacturers and urban dwellers, the second industrial revolution introduced mass-produced goods into an increasingly technologically dependent and international market. The rise of mass-produced sewing machines, automobiles, electrical lighting systems, and communications marked a profound transformation of methods of production and economics, becoming a major contributor to national economies in America and its European competitors. Manufacturing in the United States steadily climbed while the percentage of Americans working in agriculture declined from 84 percent in 1800 to less than 40 percent in 1900.

Three closely related factors—industrialism, nationalism, and imperialism—soon combined to reinforce American enthusiasm for technology as a key element of national policy. By the end of the nineteenth century, the first industrial revolution (begun in England and concerned with adding steam power to manufacturing) yielded to a larger, globally oriented second industrial revolution, linked to broader systems of technological production and to imperialistic practice. In contrast to the first industrial revolution, which was regional and primarily affected manufacturers and urban dwellers, the second industrial revolution introduced mass-produced goods into an increasingly technologically dependent and international market. The rise of mass-produced sewing machines, automobiles, electrical lighting systems, and communications marked a profound transformation of methods of production and economics, becoming a major contributor to national economies in America and its European competitors. Manufacturing in the United States steadily climbed while the percentage of Americans working in agriculture declined from 84 percent in 1800 to less than 40 percent in 1900.

The second industrial revolution caused three important changes in the way Americans thought about the world and the best ways they could achieve national goals. First, the process of rapid industrialism brought about a heightened standard of living for many Americans, creating for the first time a distinct middle class. By the turn of the twentieth century, the architects of the interlocked technological systems that had made the United States an economic powerhouse—from the steel magnate Andrew Carnegie to the oil baron John D. Rockefeller and the inventor and electrical systems creator Thomas Alva Edison—were increasingly represented in Washington, and their concerns helped shape foreign policy discussions. Second, and closely related, industrialization heightened an emerging sense of national identity and professionalization among citizens in the leading industrialized nations. The rise of nationalism was fueled not only by the technologies that these system builders created, but by other technologies and systems that rose with them, including low-cost mass-circulation newspapers, recordings of popular songs and national anthems, and public schools designed to instill in pupils the work ethic and social structure of the modern factory. The late nineteenth century was also the time that national and international scientific societies were created. American science was growing through the increasing numbers of young scientists who flocked to European universities to earn their Ph.D.s, carrying home a wealth of international contacts and commitments to higher standards. It was no coincidence that the rise of professional scientific communities paralleled the expanding middle class, as both groups found common support in the expansion of land-grant and private universities and in the industrial opportunities that awaited graduates of those universities. These new networks crystallized swiftly: they included the American Chemical Society (1876), the International Congress of Physiological Sciences (1889), the American Astronomical Society (1899), and the International Association of Academies (1899). The American Physical Society (1899) was founded two years before the federal government created the National Bureau of Standards, reflecting growing concerns from industrialists about creating international standards for manufacture.

Finally, the rise of advanced capitalist economies came to split the globe into "advanced" and "backward" regions, creating a distinct group of industrial nations linked to myriad colonial dependencies. Between 1880 and 1914 most of the Earth's surface was partitioned into territories ruled by the imperial powers, an arrangement precipitated by strategic, economic, and trade needs of these modern states, including the securing of raw materials such as rubber, timber, and petroleum. By the early 1900s, Africa was split entirely between Britain, France, Germany, Belgium, Portugal, and Spain, while Britain acquired significant parts of the East Asian subcontinent, including India. The demands of modern technological systems both promoted and reinforced these changes. The British navy launched the HMS Dreadnought in 1906, a super-battleship with greater speed and firing range than any other vessel, to help maintain its national edge and competitive standing among its trade routes and partners, while imperialistic relations were maintained by technological disparities in small-bore weapons. One was a rapid-fire machine gun invented by Sir Hiram Maxim, adapted by British and European armies after the late 1880s. Its role in the emerging arms race of the late nineteenth century was summed in an oftrepeated line of doggerel: "Whatever happens we have got/The Maxim gun and they have not."

RELATED VIDEO

The Long Depression was a worldwide economic recession, that began in 1873 and ended around 1896. It was the most severe in Europe and the United States, which had been experiencing strong economic growth fueled by the Second Industrial Revolution in the decade...

The Long Depression was a worldwide economic recession, that began in 1873 and ended around 1896. It was the most severe in Europe and the United States, which had been experiencing strong economic growth fueled by the Second Industrial Revolution in the decade...