This section of the Long, Long Trail will be helpful for anyone wishing to find out about the fighting in France and Flanders.

This section of the Long, Long Trail will be helpful for anyone wishing to find out about the fighting in France and Flanders.

What was the Western Front?

The Western Front was the name applied to the fighting zone in France and Flanders, where the British, French, Belgian and (towards the end of the war) the American armies faced that of Germany. There was an Eastern Front too, in Poland, Galicia and down to Serbia, where Russian armies faced those of Germany and Austria-Hungary. The Western Front was not the only theatre that saw the British army in action during the Great War but it was by far the most important. After the battles of 1914 both sides held an entrenched line that stretched from Nieuport on the Belgian coast, through the flat lands of industrial Artois, continuing through the wide expanses of the Somme and Champagne, into the high Vosges and on to the Swiss border. The British held a small portion of this 400-mile long line, varying from some 20 miles in 1914 to over 120 early in 1918.

A summary of the war on the Western Front

From the moment the German army moved quietly into Luxemburg on 2 August 1914 to the Armistice on 11 November 1918, the fighting on the Western Front in France and Flanders never stopped. There were quiet periods, just as there were the most intense, savage, huge-scale battles. Until mid-1917 when the French Army was seriously affected by mutiny, the British Expeditionary Force was the junior partner. From that time until the ultimate victory, the British army played the central role. Weakened by casualties and government action that made the army a low priority for the national manpower, with an ever-lengthening line to hold, the BEF fought a magnificent defence in spring 1918. Breakthrough came August 1918 and in the last 100 days of the war the BEF spearheaded the defeat of the main body of the main enemy.

The war on the Western Front can be thought of as being in three phases: first, a war of movement as Germany attacked France and the Allies sought to halt it; second, the lengthy and terribly costly siege warfare as the entrenched lines proved impossible to crack (late 1914 to mid 1918); and finally a return to mobile warfare as the Allies applied lessons and technologies forged in the previous years.

Why did war come to France and Flanders?

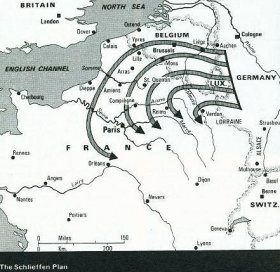

Decades before the Great War, Germans knew they would one day fight a major war in Europe. They faced the possibility of encirclement, a threat which became real when France allied with Russia. The staff of the army under von Schlieffen proposed a breathtaking plan (compiled in the early years of the century) that would defeat both of these long-term enemies. It was considered that Russia would be slow to mobilise it's armies, giving time for Germany to attack France. France would need to be quickly defeated, allowing Germany to turn it's attentions to the Russian Bear.

The von Schlieffen plan therefore proposed for a rapid advance, with German troops sweeping through neutral Belgium, swinging west along the North Sea coast and then to the west of Paris. (Schlieffen also planned to strike into the Netherlands to capture Antwerp from the North; his successor von Moltke cancelled this only because of a lack of artillery). French plans played into German hands, as they proposed to launch attacks into Alsace and Lorraine.

British battles and engagements

British battles and engagements

The Long, Long Trail, being a website about the British army, does not cover the struggles between the French and Germans, nor the role of the Belgian army, except to provide context.

In 1921, to make some sense for historical description of these continual and complex battles, the various actions involiving the British army were defined and named by the Battles Nomenclature Committee. It is their definitions that are used throughout this site. The early battles were of a very small in scale compared to the immense affairs of later in the war. Nonetheless, for the army that was present at the time these actions were of great importance, and they are all listed accordingly.

First phase: a war of encounter and movement, in which preconceptions are destroyed

Second phase: entrenched siege warfare in which British work to French strategy

By the end of First Ypres, the two sides were deadlocked and in siege warfare. The continuous trench lines of the Western Front presented all army commanders with a dilemma. The proven way to win battles was to 'turn the flank' of the enemy (that is, to go around his position). But there was no flank on the Western Front, for either side. At one end was the North Sea, at the other end 400 miles away, the Alps. The front settled into a period of trench warfare. The British army was still very much the junior partner on land, and took part in many attacks of increasing scale as the army grew in size. Casualties were very high for little gained in terms of territory. It is often argued, however, that the searing experience of these battles forced the army to develop into the modern age of technological warfare.

Under the command of Sir John French up to October 1915, the BEF lost the core of the pre-war regular army while being greatly outmanned and outgunned. It became clear that the enemy positions could be broken into, but not broken through, without the deployment of much larger forces. Under Sir Douglas Haig, most of the New Armies fought their first major engagement on the Somme.

This phase of the war was a time of great and rapid technological and tactical development: poison gas, flame-throwers, and grenades (in 1915), tanks and ground support from aircraft (in 1916), predicted artillery and machine gun barrages (developed from mid-1916). Equally, sophisticated defence was developed, including extensive use of underground works, concrete shelters and emplacements, counter-battery artillery fire, and mining (which was also used offensively).

Third phase: entrenched siege warfare in which British begin to play the leading role

The experience of the Somme caused the Germans to reconsider their strategy on the Western Front. They constructed a formidably strong defensive position many miles in the rear, and withdrew to it in early 1917. The British called the part that they face the Hindenburg Line. A large French offensive, supported by a British attack at Arras, withered against the new German defence and many French units had had enough. Many of them mutinied. From this moment in May 1917 the British army had no choice but to take the lead role while the French stood on the defensive. The main British effort of the year was the costly and depressing Third Ypres, while at Cambrai a significant new tactical approach pointed the way to ultimate victory.

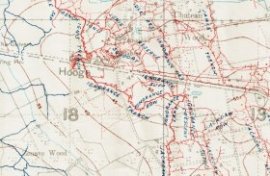

A section of the formidable defensive positions faced by the British army when it attacked at Ypres on 31 July 1917

Final phase: return to open warfare

It was revolution in Russia that changed the nature of the attritional deadlock in the west. Fighting in the east stopped in late 1917, allowing the Germans to transfer many Divisions to the Western Front. They knew that time was running out, for the United States of America had now entered the war on the Allied side and it was only a matter of time before vast untapped reserves of manpower swung the balance in favour of the Allies.

RELATED VIDEO

Following the outbreak of World War I in 1914, the German Army opened the Western Front by first invading Luxembourg and Belgium, then gaining military control of important industrial regions in France. The tide of the advance was dramatically turned with the Battle...

Following the outbreak of World War I in 1914, the German Army opened the Western Front by first invading Luxembourg and Belgium, then gaining military control of important industrial regions in France. The tide of the advance was dramatically turned with the Battle...