Redactions

Redactions

Let’s get this out there: I’m a confessed “Archive Rat.” While I may not actually be thrilled while in the archives themselves (which are often dusty, bureaucratic, uncomfortable places), I love the thrill of finding something old, something new, something once secret. I get a lot out of that, and I love having thousands of documents at my fingertips, digitized and easy to search. This is a fortunate thing, because if you want to do the history of the bomb, you’d better love sifting through paperwork — because there’s a lot of it.

The Big Science of the atomic bomb was accompanied by a Big Bureaucracy, the majority of which was kept in secret. This turns out to be great for historians, even if it was arguably lousy for the nation. As Richard G. Hewlett, put it the first volume of his official history of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission:

The records have survived. For this, scholars can thank two much-maligned practices of the bureaucracy: classification and multiple copies. Classified documents endure; they do not disappear from the files as souvenirs. As for copies in sextuplicate, their survival is a matter of simple arithmetic. If the original in one agency is destroyed, the chances are better than even that one of the five carbons will escape the flames in another.

What Hewlett doesn’t say here is that the reason people don’t take them home as souvenirs, or throw them out haphazardly, or lend them to their friends, or accidentally mutilate or staple them, is that because the maximum penalty for doing these sorts of things was death for much of the Cold War.

In this spirit, once a week I will pick out an interesting or exceptional document from my research database and share it with you here, with a little contextualization and commentary.

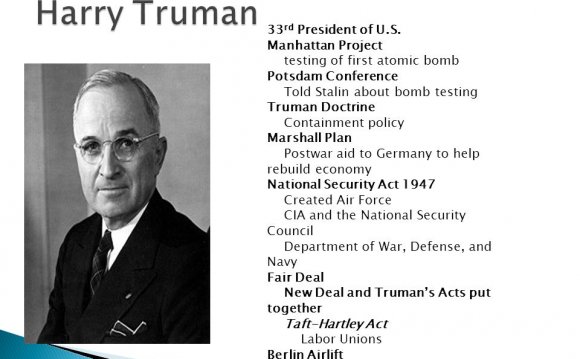

I want to start with a favorite: a series of press releases written by William L. Laurence to be sent out after the Trinity test in July 1945. Laurence, as I mentioned earlier this week, was the only newspaper reporter brought in to view the Manhattan Project. General Groves had decided that Laurence, a science journalist at the New York Times, would be useful for writing press releases, newspaper articles, and official statements. (He soon discovered Laurence was lousy at the latter — too “gee-whiz!” — and assigned those duties to Arthur W. Page, the Vice President of Marketing at AT&T and a close friend of the Secretary of War.)

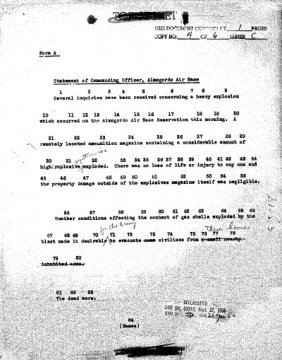

One of Laurence’s duties was to compose a series of press releases issuing cover stories for the Trinity test. The Manhattan Project folks knew that Trinity would make a big noise, and so they needed some sort of excuse — an exploding ammunition dump, for example — to give out immediately afterwards to the surrounding area. What they didn’t know was how big of a noise it was going to be, so Laurence wrote up a series of escalating press releases depending on how awful the test was.

I’ve also included what appears to be the instructions to Laurence about the statements from the Interim Committee (who gave him the assignment).

I love the ramp up here, from Form A — “no loss of life nor injury” — through Form C — “Among the dead were…” — to Form D — “caused serious damage in some sections of the communities in the area.” It’s a bit grotesque, no? Fantasies about worst case scenarios, rendered in bland bureaucratese; writing press releases that predict the author’s (Laurence’s) own death. One wonders how different our story of the bomb would be if the latter messages were among the ones to be released, and not Form A.

Next week I’ll be posting a large list of online databases for looking up bomb documents — including the one cited here — so don’t miss it.

RELATED VIDEO