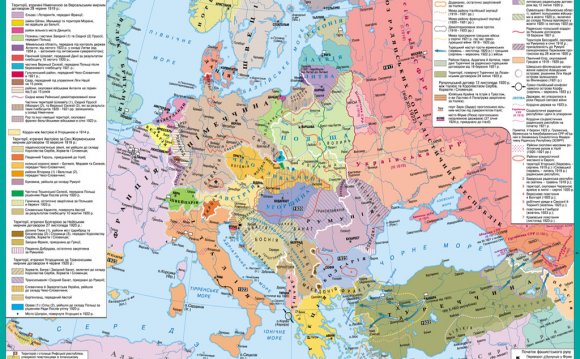

Professor David Stevenson explains how the Treaty of Versailles, the Treaties of Saint-Germain and Trianon and the Treaties of Neuilly and Sèvres re-drew Europe's post-war boundaries.

The task of drawing Europe’s post-war borders fell primarily to the Paris Peace Conference of 1919-20. There the victorious countries’ leaders drafted the Treaty of Versailles with Germany, and those of Saint-Germain with Austria, Trianon with Hungary, Neuilly with Bulgaria, and Sèvres with Turkey. But elsewhere across Europe, from Ireland to Russia, successor conflicts recast frontiers by violence.

The Paris Peace Conference

The conference agenda was set partly by the armistice agreements. Under their terms the European Allies had accepted most of the Fourteen Points, the idealistic peace programme set out by President Wilson in January 1918. It included creating a League of Nations, and envisaged only modest Allied territorial gains. But the armistices also enabled the European Allies to occupy much of the territory that they coveted, and at the conference Wilson confronted the British, French, and Italian Prime Ministers, David Lloyd George, Georges Clemenceau, and Vittorio Orlando. The treaty terms would be harsher than the Central Powers had expected, but they had little alternative to accepting them.

Georges Clémenceau leaves the Peace Conference

French Prime Minister, Georges Clémenceau, pictured in July 1919 leaving the Paris Peace Conference.

View images from this item (1)The Treaty of Versailles

Under the Versailles Treaty, Germany lost about a tenth of its territory. It gave up Alsace-Lorraine, and ceded the Saar coalfield to an international administration under the League. Germany lost Eupen-Malmédy to Belgium and northern Schleswig/Slesvig to Denmark. In the east it lost the ‘Polish corridor’ (which gave Poland access to the Baltic by dividing East Prussia from the rest of Germany) and Danzig, which became self-governing under the League. Although most of the populations ceded were non-German speakers, the losses were bitterly resented. Plebiscites were held along the Polish frontier and in Schleswig/Slesvig, where both sides campaigned vigorously. And although the Rhineland stayed in Germany, the area west of the river and a fifty-kilometre strip east of it were demilitarized. Germany could neither garrison nor fortify them, and the Allies would occupy them for up to 15 years. Moreover, Germany kept only small and weak armed forces and it had to pay reparations (financial compensation) to the countries it had invaded and whose ships it had sunk, this being justified by the notorious ‘war-guilt clause’ (Article 231), which blamed the war on Germany’s and its partners’ aggression.

The treaties of Saint-Germain and Trianon

The treaties with Austria and Hungary were largely predetermined – the Dual Monarchy had broken up, and new states had taken over. The Allies could not have recreated Austria-Hungary even had they wanted. However, they further decided that the newly established Austrian Republic could not unite with Germany and that the German-speakers in the Sudetenland should be included in Czechoslovakia. Millions of ethnic Germans would therefore remain outside Germany’s borders, and many of them under foreign rule. Similarly the new state of Hungary shrank drastically, and many Magyars lived outside it. In the Adriatic, a dramatic clash came over Fiume (Rijeka), which had a majority of Italian-speakers although its suburbs were South Slav. When Italy claimed it, Wilson publicly opposed the demand, and Orlando walked out of the conference. Eventually Italy did gain Fiume, although overall it received less than it had been promised before entering the war, thus leaving another major country dissatisfied.

RELATED VIDEO